We Are Servants of Our Formulaic Ways Art Drawings

Understanding Egyptian art lies in appreciating what information technology was created for. Ancient Egyptian fine art must be viewed from the standpoint of the ancient Egyptians not from our viewpoint. Here we explore the basis of Egyptian art.

Defining Way

Agreement Egyptian art lies in appreciating what it was created for. Ancient Egyptian art must be seen from the viewpoint of the ancient Egyptians, not from ours.

The somewhat static, formal, abstruse, and oft blocky nature of much of Egyptian imagery has led to information technology being compared unfavourably with more 'naturalistic,' Greek or Renaissance art. Only the art of the Egyptians served a different purpose than that of these later cultures.

Another problem is 'What do nosotros mean by Fashion?'

- Was the Egyptian 'way' different from today's view of 'style'?

Style is defined as 'how you do something.' Fashion should exist distinctive and recognisable. It is derived from the Latin stylus,meaning writing implement, and was first concerned with the different writing of individuals. In art there are two aspects to way and sometimes one style dominates. In Egyptian fine art that is the example.

The first aspect is the individual style of the artist. This can exist hard to determine with some cultures, and is by and large indicated by the methods used to produce the art. This area of mode can be divided into assertive fashion which is personal to the artist and carries information supporting individual identity so in that location is emblemic style which carries information about the group identity of the society the artist belongs to.

The second aspect of style is concerned with stylistic culture and is really a style of communicating or tranfering information. Egyptian fine art is dominated by this stylistic aspect.

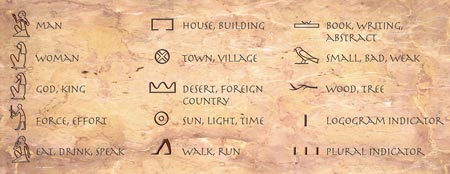

What is striking about Egyptian art is that text accompanied nearly all images. In statues the identifying text will appear on a back pillar supporting the statue or on the base of operations. Relief or paintings usually have captions or longer texts that elaborate and complete the story in the scenes. Paintings and panels are frequently accompanied past hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphs are frequently works of art in themselves, fifty-fifty though many are instead phonetic sounds. Some stand for an object or concept which we call logographic which is a graphic that represents a word (Effigy 1). Today the modern symbols used on road signs would exist logograms.

Figure ane: Egyptian logograms. Peter Bull.

When looking at a piece of Egyptian art the text and image are non ever clearly defined for case the determinative (a sign at the terminate of a give-and-take that indicates identification of motion is determined by a pair of legs and the name of a man is shown past the image of a human being).

The exception to this Egyptian manner is the art from the period of Akhenaten (1352 – 1336 BCE). He rejected the pantheon of gods in favour of one god and along with that radical move the art from this reign was different.

The proportions of the human form are seen in farthermost with big heads and drooping features, narrow shoulders and waist, pocket-sized torso, big buttocks, drooping belly and curt arms and legs. We do not know why there was such a radical change, and after his reign the art reverted to classical forms (Figure 2).

a) b)

b)

Figure 2: a) Rameses II compared with b) Akhenaten, note the differences. a) © The Trustees of the British Museum, b) © The Art Archive / Alamy

Egyptian Style in Statues

While today we marvel at the glittering treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamen, the cute reliefs in the New Kingdom tombs, and the serene beauty of Old Kingdom statues, information technology is important to retrieve that the majority of these works were never intended to be seen, that was not their purpose. So when nosotros look at them for mode nosotros can know the person by interpreting the accompanying hieroglyphs, but the fashion of ornament is as well singled-out and tells u.s.a. something about the society.

- What was singled-out nearly the style of the Egyptian fine art?

- Can we place the conventions and, if then, what are they?

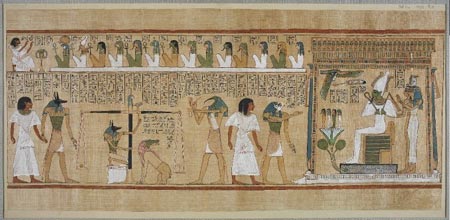

These images of high-status people, whether statues of gods or pharaohs or reliefs on tomb walls, were designed to benefit a divine or deceased recipient. The bulk of Egyptian art exhibits frontality. This only means they face direct ahead with just i eye visible and both shoulders front end facing and this can make them look rigid (Figure 3).

- Were at that place other conventions of manner in Egyptian art?

Figure 3: Egyptian Book of the Dead showing the stylistic features. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The principal conventions of Egyptian fine art can exist seen in Figure 3 to a higher place. Stylistic conventions adopted past every creative person in ancient Egypt included not only 'Frontality' but too 'Axiality'. The rules of axiality meant figures were placed on an axis.

Proportions of figures were related to the width of the palm of the hand then there were rules well-nigh proportions of head to body. The faces did non express emotions.

The sizes of figures were determined by their importance. The proportions of children did not change; they are only depicted smaller in scale. Servants and animals were normally shown in smaller scale. In lodge to clearly define the social hierarchy of a situation, figures were drawn to sizes based not on their distance from the painter's signal of view but on relative importance. For case, the Pharaoh would exist drawn every bit the largest figure in a painting no affair where he was situated, and a greater God would exist drawn larger than a lesser god.

Axiality, proportion and hieratic scaling signal that Egyptian artists would accept had to use mathematics to construct their composition. Ancient Egyptian artists used vertical and horizontal reference lines in gild to maintain the correct proportions in their work. In many tombs the walls nevertheless conduct these grids used to ensure the conventions were kept to by the lower and apprentice artists working for the master artist. Political and religious, too as artistic order was maintained in Egyptian fine art.

Important figures were not unremarkably depicted overlapping, simply figures of servants were. Each object or element in a scene was designed and drawn from its most recognizable angle. The objects in a scene were and so grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but the heart and shoulders are shown facing frontally. These scenes are blended images designed to provide complete information well-nigh the human relationship of the objects to each other, rather than from a single viewpoint.

Rules were also practical to the poses and gestures of the figures to reflect the pregnant of what the person was doing. An ancient Egyptian artist would depict a figure in an act of worship with both arms extended forward with hands upraised.

They did non attempt to replicate the real earth but did achieve a realistic dialogue betwixt the iii dimension world and their paintings past the use of position and grouping to stand for depth and so the background is shown to a higher place the figure the foreground below or to one side.

Most formal statues testify a prescribed frontality, meaning they are arranged to look direct ahead, because they were designed to face the ritual being performed earlier them.

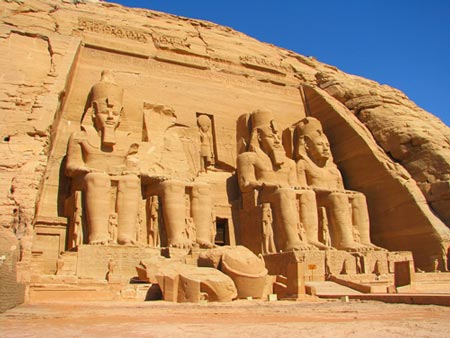

Frequently this is in a temple or tomb such every bit the row of four jumbo statues of Rameses II outside the main temple at Abu Simbel (Figure 4). They were designed to face the rising dominicus and so important in Egyptian religion.

Figure iv: Statues of Rameses II at Abel Simbel. © Shutterstock.

Statues were gear up to take part in the rituals relating to the gods and the pharaoh. Many statues were too originally placed in recessed niches or other architectural settings; contexts that would brand frontality their expected and natural manner. Others were placed confronting pylons or along an artery to the temple as in Figure five.

Figure 5: Avenue of Sphinxes and first pylon at western archway to Precinct of Amun Re Karnak Temple. © Shutterstock

Statuary, whether divine, royal, or elite, provided a conduit for the spirit (or ka) of the represented being to interact with the earthly realm. Divine cult statues (few of which survive) were the subject of daily rituals. Those rituals would include those of clothing, anointing, and perfuming with incense the statue. Sometimes they came out of the temple and were carried in processions for special festivals, and then that the people could "see" them even though they were almost all entirely shrouded from view in wooden arks, but their 'presence' was felt.

The reason for this frontality is they were designed not as an art course only as part of a religious ritual. The Egyptians did not accept a word for fine art simply they had words for statue, stelae or tomb. They had a sense of the aesthetic but within a function. Art is then functional within the faith.

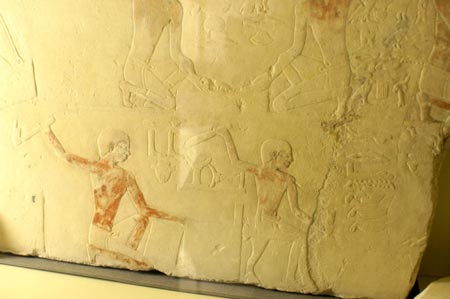

Woods and metal statuary to represent generic figures and these in contrast to the ritual statues were more expressive. The arms could be extended and hold separate objects, spaces betwixt the limbs were opened to create a realistic appearance, and more positions were possible. Even and then the art conventions were kept to (Figure 6).

Effigy 6: Relief of craftmen. Pat O'Brien

Stone, wood, and metal statuary of elite figures all served the same functions and retained the same type of formalization and frontality. Merely statuettes of lower status people displayed a wide range of possible actions, and these pieces were focused on the actions, which benefitted the aristocracy owner, not the people involved.

Hence these generic figures were frequently put in tombs to serve the tomb owners in the afterlife as bakers, scribes and other occupations. They were at that place equally shabti probably developed from the servant figures common in tombs of the Middle Kingdom. They were shown as mummified similar the deceased, with their own coffin, and inscribed with a spell to provide nutrient for their master or mistress in the afterlife. Alternatively at that place can be models of the servants both sorts can be seen in Figure 7, below.

a) b)

b)

Effigy 7: a) Shabti figures; b) model of a sailing ship. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Small figures of deities, or their brute personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was frequently used for expensive versions of these; painted woods was the almost common material, and normal for the pocket-sized models of animals, slaves and possessions placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

Three-dimensional representations, while beingness quite formal, as well aimed to reproduce the real-globe—statuary of gods, royalty, and the elite was designed to convey an idealized version of that individual. Some aspects of 'naturalism' were dictated by the material. Stone statuary, for instance, was quite airtight—with artillery held close to the sides, express positions, a potent back pillar that provided back up, and with the fill up spaces left between limbs

Egypt Manner in Paintings and Relief

Paintings demonstrated 2-dimensional fine art and as a upshot it represented the earth quite differently. Egyptian artists used the two-dimensional surface to provide the near representative aspects of each object in the scene.

- Does the painted art also prove the aforementioned conventions?

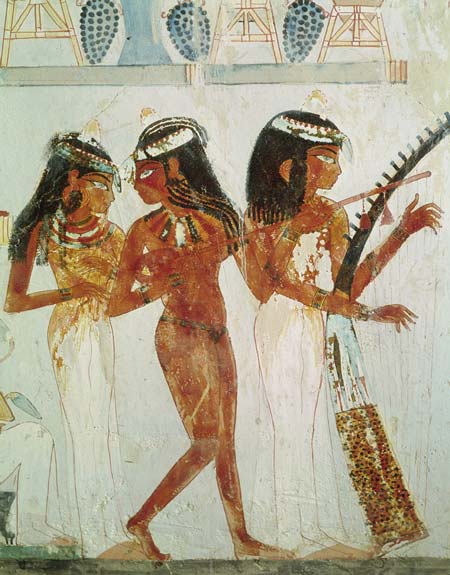

Egyptian artists worked in two dimensions only and then the best characterisation of the object was the view the creative person used. Again they used the ideas of frontality, axiality and proportionality. So when creating the human class the artist showed the head in contour with total view eye line parallel with the shoulder line while the chest, waist, hips and limbs are in profile. Withal, if at that place is neck jewellery to be shown it is shown in total (Figure eight).

Figure 8: Musicians, Tomb of Nakht. © The Art Gallery Collection / Alamy.

Scenes were ordered in parallel lines, known as registers. These registers separate the scene as well as provide ground lines for the figures. Scenes without registers are unusual and were generally only used to specifically evoke anarchy; battle and hunting scenes will often testify the prey or strange armies without basis lines. Registers were also used to convey data nearly the scenes—the higher up in the scene, the higher the status; overlapping figures imply that the ones underneath are further away, as are those elements that are higher inside the annals.

Keen observation, exact representation of actual life and nature, and a strict conformity to a set of rules regarding representation of three dimensional forms dominated the grapheme and style of the art of ancient Egypt. Abyss and carefulness were preferred to prettiness and cosmetic representation. The use of mathematics to create the art is also very evident in many of the incomplete art forms indicating that Egyptian artists used some mathematical formulas to create social club in their art.

Because of the highly religious nature of Aboriginal Egyptian civilization, many of the bully works of Ancient Egypt depict gods, goddesses, and Pharaohs, who were likewise considered divine. Aboriginal Egyptian art is characterized by the idea of order. Clear and elementary lines combined with uncomplicated shapes and flat areas of colour helped to create a sense of club and residue in the art of aboriginal Arab republic of egypt.

Symbolism played an of import role in establishing a sense of club this ranged from the pharaoh'due south regalia (symbolizing power to maintain order) to the private symbols of Egyptian gods and goddesses. Animals were also highly symbolic figures in Egyptian fine art.

Colours of the subjects were more expressive rather than natural. So a red pare implied hard working tanned youth, whereas yellow skin was used for women or middle-aged men who worked indoors. The presence of bluish or gilded indicated divinity. The use of black for royal figures expressed the fertility of the Nile. Stereotypes of people were employed to indicate geographical origins.

Difference in scale was commonly used for conveying hierarchy. The larger the scale of the figures, the more important they were. Kings were oft shown at the aforementioned scale as the deities, and both are shown larger than the elite and far larger than the general populace and in smallest scale are shown servants, entertainers, animals, trees, and architectural details. And so the size indicates relative importance in the social social club.

Ancient Egyptian fine art forms are characterized past regularity and detailed depiction of gods, human beings, heroic battles, and nature. A loftier proportion of the surviving works were designed and made to provide peace and assistance to the deceased in the afterlife. The artists' desire was to preserve everything from the present as clearly and permanently as possible. Ancient Egyptian fine art was designed to stand for socioeconomic status and conventionalities systems.

The Egyptians used the distinctive technique of sunken relief, well suited to very vivid sunlight. The main figures in reliefs attach to the aforementioned figure convention as in painting.

Papyrus was used by ancient Egyptians and information technology was exported to many states in the ancient globe for writing and painting. Papyrus is a relatively fragile medium generally lasting effectually a century or two in a library, and though used all over the classical world has but survived when cached in very dry out conditions, and and so, when plant, is often in poor condition.

Source: https://edu.rsc.org/resources/principles-of-egyptian-art/1622.article

0 Response to "We Are Servants of Our Formulaic Ways Art Drawings"

Post a Comment